|

|

|

Home | Boating | Fishing | Diving | Water Sports | Safety | Environment | Weather | Photo Blog | Add Your Company to the Directory |

| You Are Here > Home > Marine Environment > Mangroves |

Florida

Mangroves Florida

Mangroves

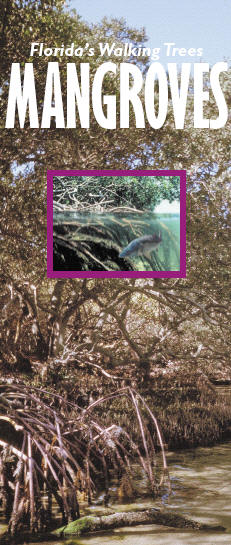

What are Mangroves? Florida’s estimated 400,000–500,000 acres of mangrove forests contribute to the overall health of the state’s southern coasts. Mangroves trap and cycle pollutants, chemical elements, and inorganic nutrients. Mangrove roots not only act as physical traps but also provide attachment surfaces for marine organisms such as barnacles and oysters. Many of these attached organisms, especially blue-green algae, filter water and trap and cycle nutrients. The importance of mangroves to their associated marine life cannot be overemphasized. Mangroves provide protected nursery areas for fish, crustaceans, and shellfish. They also function as the basis of the food chain for a multitude of marine species such as snook, snapper, tarpon, jack, sheepshead, red drum, oysters, crabs, and shrimp. Florida’s important recreational and commercial fisheries will drastically decline without healthy mangroves. Animals find shelter in mangrove roots and branches, and the branches serve as rookeries (nesting areas) for coastal birds such as egrets, herons, brown pelicans, and roseate spoonbills. Many migratory birds also depend on large mangroves for food and shelter.

Each of these species has a remarkable method of propagation during which seedlings, or propagules, are formed. On red mangrove trees, seedlings are germinated while still attached to the tree and are contained within a fruit cover. Over time, the fruit cover withers away, and the seedling is forced from the tree by strong winds or high tides. The seedlings then float for a while and eventually settle on a shallow shoreline. Seedlings of both black and white mangroves also form on the tree within a fruit cover but drop with the cover intact. The propagule may lose the fruit cover while floating in the water or when it reaches a shoreline. Florida’s mangroves are tropical species and are sensitive to temperature fluctuations as well as to freezing temperatures. Mangroves are common as far north as Cedar Key on the gulf coast and Cape Canaveral on the Atlantic coast. Black mangroves can occur farther north in Florida than the other two species. Frequently, all three species grow intermixed without any perceptible zonation. People living along south

Florida coasts benefit in many ways from mangroves. In addition

to providing fish habitats, mangrove forests protect uplands

from storm winds, waves, and floods. The amount of protection

afforded by mangroves depends upon the width of the forest. A

very narrow fringe of mangroves offers less protection, but a

wide expanse of forest can absorb wave energy and thus

considerably reduce water damage to property. Mangroves help

prevent erosion by stabilizing shorelines with their specialized

root systems. They also remove pollutants and, by slowing wave

action, maintain water quality and clarity. |

Mangrove Losses in Florida Although mangroves can be damaged by natural events, human destruction of mangroves has been extensive. Scientists at the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s Florida Marine Research Institute use a geographic Information System to study changes in Florida’s coastal habitats. By comparing digitized aerial photographs from different years, and by researching the history of the study sites, the scientists are able to evaluate changes in the extent of mangrove forest. These studies show that mangrove acreage has been lost, often because of human activities. Tampa Bay, located on the southwest Florida coast, has experienced considerable change. The Port of Tampa is one of the 15 largest ports in the nation. Over the past 100 years, Tampa Bay has lost over 40% of its coastal wetlands, including both mangroves and salt marshes. The next large bay system south of Tampa Bay is Charlotte Harbor. Unlike Tampa Bay, Charlotte Harbor is a less urbanized estuary, but some mangrove destruction has occurred here as well. Punta Gorda warfront development accounts for 59% of the total loss in Charlotte Harbor. Mangrove acreage has increased in parts of the Harbor, probably as a result of sediments being disturbed during development. As tidal flats recovered more sediment, they were colonized by mangroves; tidal-flat acreage decreased, and mangrove acreage increased. Spoil islands, created as by-products of channel dredging, also provide suitable habitat for mangroves. Scientists have also been observing changes in the Lake Worth system on the southeast Florida coast. Lake Worth, near West Palm Beach, evolved naturally from a saltwater lagoon to a freshwater lake, but because of human alterations, the lake has again become an estuarine lagoon. Exotic vegetation and urbanizing have replaced the mangroves, whose acreage has decreased 87% over the past 40 years. The 276 acres mangroves that remain are found in small scattered areas and are now protected by strict regulations. Another study site included the Indian River Lagoon from St. Lucie Inlet north to Satellite Beach. The Indian River is the longest saltwater lagoon in Florida. The study site contains almost 8,000 acres of mangroves, but only 1,900 acres are available as fisheries habitat because the remainder are mosquito impoundments. Consequently, 76% of the existing mangrove areas are not productive to fisheries. Since the 1940s, 86% of the mangrove habitat areas have been lost. Mangroves are Florida’s true natives and are part of our state heritage. It is up to us to ensure a place for them in Florida’s future as one of our most valuable coastal resources. State and local regulations have been enacted to protect Florida’s mangrove forests, and local laws vary. Prior to taking any action, be sure to check with officials in your area to determine whether a permit is required. Trimming of mangroves is permitted only in accordance with the Mangrove Trimming and Protection Act of 1996. Text and images on this page provided by the Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission and the Florida Marine Research Institute.

|

|

Privacy Policy |

Advanced

Search |

Photo Gallery

|

Add Your

Company To The Directory

|

Contact Us

|

Advertise |